by Rahul Vohra, the founder and CEO of Superhuman

We’ve all heard that product/market fit drives startup success — and that the lack thereof is what’s lurking behind almost every failure.

For founders, achieving product/market fit is an obsession from day one. It’s both the hefty hurdle we’re racing to clear and the festering fear keeping us up at night, worried that we’ll never make it. But when it comes to understanding what product/market fit really is and how to get there, most of us quickly realize that there isn’t a battle-tested approach.

In the summer of 2017, I was waist-deep in my search for a way to find product/market fit for my startup, Superhuman. Turning to the classic blog posts and seminal thought pieces, a few observations stuck out to me. Y Combinator founder Paul Graham described product/market fit as when you’ve made something that people want, while Sam Altman characterized it as when users spontaneously tell other people to use your product. But of course, the most cited description comes from this passage in Marc Andreessen’s 2007 blog post:

“You can always feel when product/market fit is not happening. The customers aren’t quite getting value out of the product, word of mouth isn’t spreading, usage isn’t growing that fast, press reviews are kind of ‘blah,’ the sales cycle takes too long, and lots of deals never close.

And you can always feel product/market fit when it is happening. The customers are buying the product just as fast as you can make it — or usage is growing just as fast as you can add more servers. Money from customers is piling up in your company checking account. You’re hiring sales and customer support staff as fast as you can. Reporters are calling because they’ve heard about your hot new thing and they want to talk to you about it. You start getting entrepreneur of the year awards from Harvard Business School. Investment bankers are staking out your house.”

For me, this was the most vivid definition — and one that I stared at through tears.

We had set up shop and started coding Superhuman in 2015. A year later, our team had grown to seven and we were still furiously coding. By the summer of 2017, we had reached 14 people — and we were still coding. I felt intense pressure to launch, from the team and also from within myself. My previous startup, Rapportive, had launched, scaled and been acquired by LinkedIn in less time. Yet here we were, two years in, and we had not passed go.

But no matter how intense the pressure, I wasn’t ready to launch. Common practice would be to “throw it out there and see what sticks,” which may be fine after a few months of effort when the sunk cost is low. But the “launch and see what happens” method seemed irresponsible and reckless to me — especially given the years that that we had invested.

%20(1).jpg)

Further compounding the pressure, as a founder, I couldn’t just tell the team how I felt. These super-ambitious engineers had poured their hearts and souls into the product. I had no way of telling the team we weren’t ready, and worse yet, no strategy for getting out of the situation — which is not something they would want to hear. I wanted to find the right language or framework to articulate our current position and convey the next steps that would get us to product/market fit, but was struggling to do so.

That’s because the descriptions of product/market fit I found were immensely helpful for companies post-launch. If, after launch, revenue isn’t growing, raising money is tough, the press doesn’t want to talk to you and user growth is anemic, then you can safely conclude you don’t have product/market fit. But in practice, because of my previous success as a founder, we didn’t have problems raising money. We could have gotten press, but we were actively avoiding it. And user growth wasn’t happening because we deliberately choosing not to onboard more users. We were pre-launch — and we didn’t have any indicators to clearly illustrate our situation.

The descriptions of product/market fit all seemed so post hoc, so unactionable. I had a clear understanding of where we stood, but I had no way of conveying that to others — and no plan for the part that should come next.

So I racked my brain for an answer on how to travel the distance between where Superhuman was and the high bar that we needed to hit. And I eventually started to wonder: what if you could measure product/market fit? Because if you could measure product/market fit, then maybe you could optimize it. And then maybe you could systematically increase product/market fit until you achieved it.

Reoriented around this purpose and reinvigorated by the new direction, I set out to reverse engineer a process for getting to product/market fit. Below, I outline the findings that followed, specifically unpacking the clarifying metric that made everything fall into place and the four-step process we used to build an engine that propelled Superhuman forward on the path to finding our fit.

ANCHORING AROUND A METRIC: A LEADING INDICATOR FOR PRODUCT/MARKET FIT

On my quest to understand product/market fit, I read all I could and spoke with every expert I could find. Everything changed when I found Sean Ellis, who ran early early growth in the early days of Dropbox, LogMeIn, and Eventbrite and later coined the term “growth hacker.”

The product/market fit definitions I had found were vivid and compelling, but they were lagging indicators — by the time investment bankers are staking out your house, you already have product/market fit. Instead, Ellis had found a leading indicator: just ask users “how would you feel if you could no longer use the product?” and measure the percent who answer “very disappointed.”

After benchmarking nearly a hundred startups with his customer development survey, Ellis found that the magic number was 40%. Companies that struggled to find growth almost always had less than 40% of users respond “very disappointed,” whereas companies with strong traction almost always exceeded that threshold.

Ask your users how they’d feel if they could no longer use your product. The group that answers ‘very disappointed’ will unlock product/market fit.

A helpful example comes from Hiten Shah, who posed Ellis’ question to 731 Slack users in a 2015 open research project. 51% of these users responded that they would be very disappointed without Slack, revealing that the product had indeed reached product/market fit when it had around half a million paying users. Today, this isn’t too surprising, given Slack’s legendary success story. Truly, this example shows just how hard it is to beat the 40% benchmark.

Inspired by this approach, we set out to measure what the responses would be for Superhuman. We identified users who recently experienced the core of our product, following Ellis’ recommendation to focus on those who used the product at least twice in the last two weeks. (At the time we had between 100 and 200 users to poll, but smaller, earlier-stage startups shouldn’t shy away from this tactic — you start to get directionally correct results around 40 respondents, which is much less than most people think.)

We then emailed these users a link to a Typeform survey asking the following four questions:

1. How would you feel if you could no longer use Superhuman? A) Very disappointed B) Somewhat disappointed C) Not disappointed

2. What type of people do you think would most benefit from Superhuman?

3. What is the main benefit you receive from Superhuman?

4. How can we improve Superhuman for you?

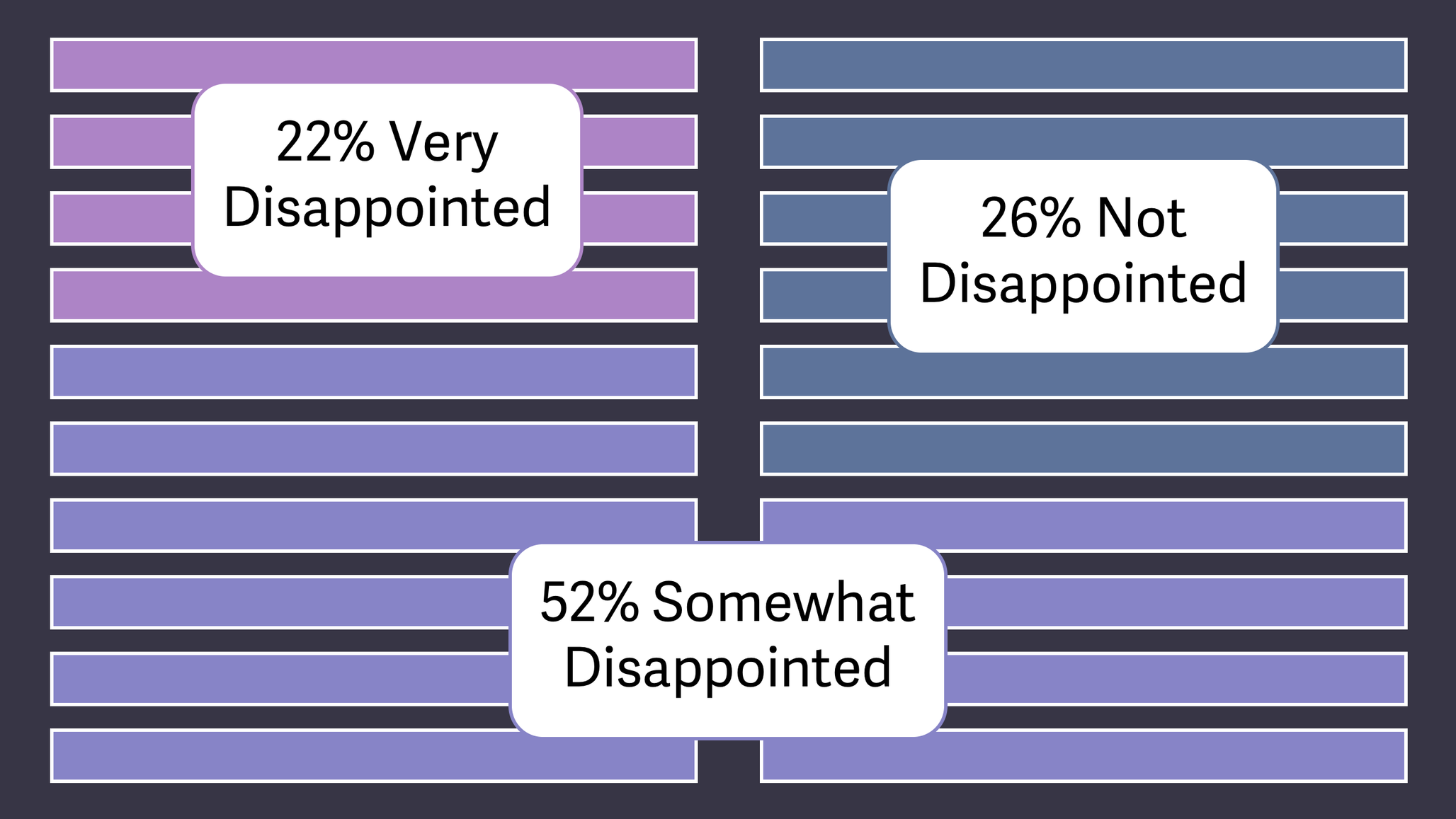

With the responses collected, we analyzed the first question:

.png)

With only 22% opting for the “very disappointed” answer, it was clear that Superhuman had not reached product/market fit. And while this result may seem disheartening, I was instead energized. I had a tool to explain our situation to the team and — most excitingly — a plan to boost our product/market fit

FROM BENCHMARK TO ENGINE: THE FOUR-STEP MANUAL FOR OPTIMIZING PRODUCT/MARKET FIT

Determined to move the needle, I became singularly focused on ways to improve our product/market fit score. The responses to each survey question would be key ingredients in what became the framework for fulfilling our goal.

Here are the four components that comprised our product/market fit engine:

1) Segment to find your supporters and paint a picture of your high-expectation customers.

With your early marketing, you may have attracted all kinds of users — especially if you’ve had press and your product is free in some way. But many of those people won’t be well-qualified; they don’t have a real need for your product and its main benefit or use case might not be a great fit. You wouldn’t have wanted these folks as users anyway.

As an early-stage team, you could just narrow the market with preconceived notions of who you think the product is for, but that won’t teach you anything new. If you instead use the “very disappointed” group of survey respondents as a lens to narrow the market, the data can speak for itself — and you may even uncover different markets where your product resonates very strongly.

For me, the goal of segmenting was to find pockets in which Superhuman might have better product/market fit, those areas I may have overlooked or didn’t think to scope down to.

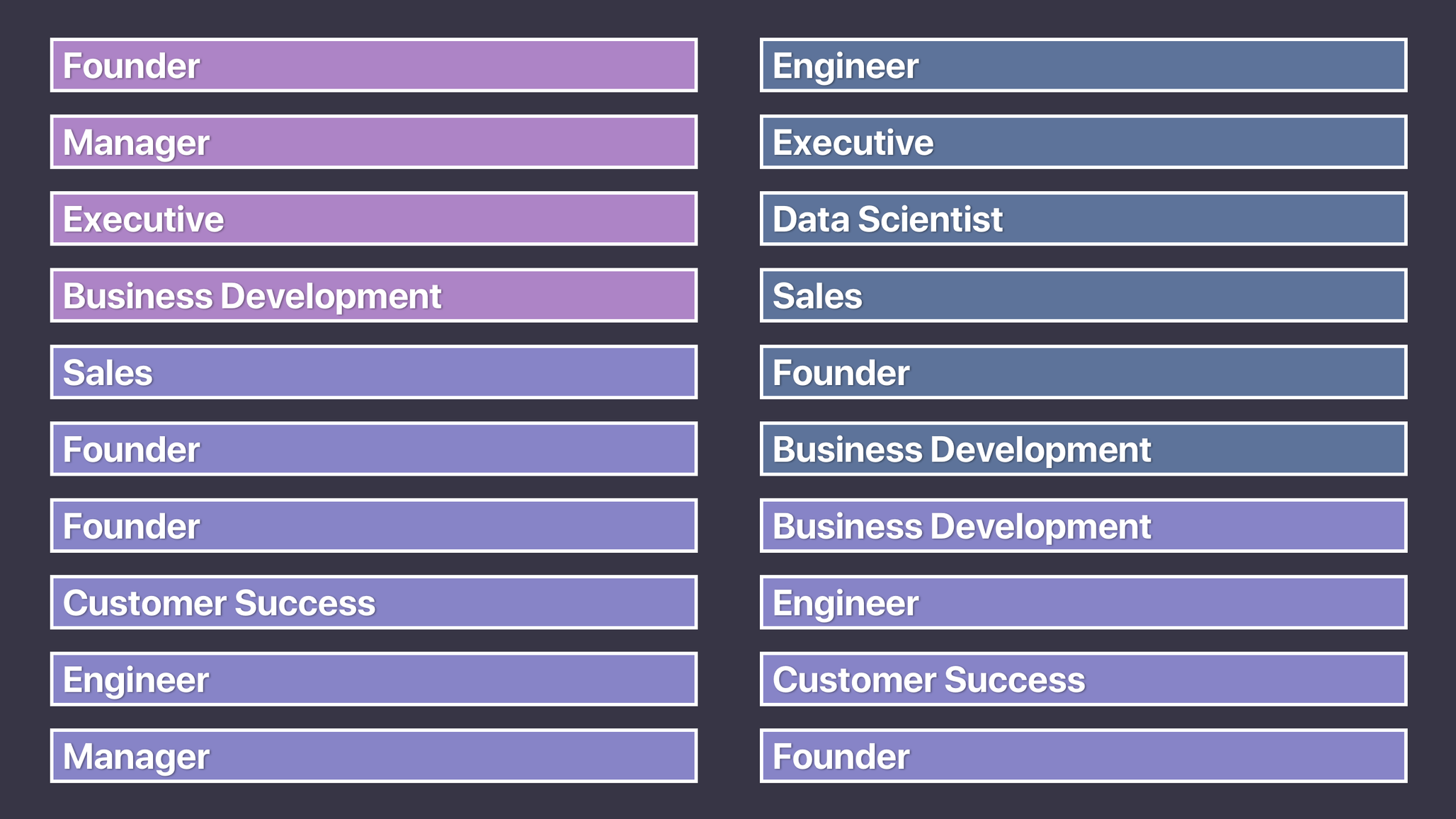

To start, we grouped the survey responses by their answer to the first question (“How would you feel if you could no longer use Superhuman?”):

We then assigned a persona to each person who filled out a survey.

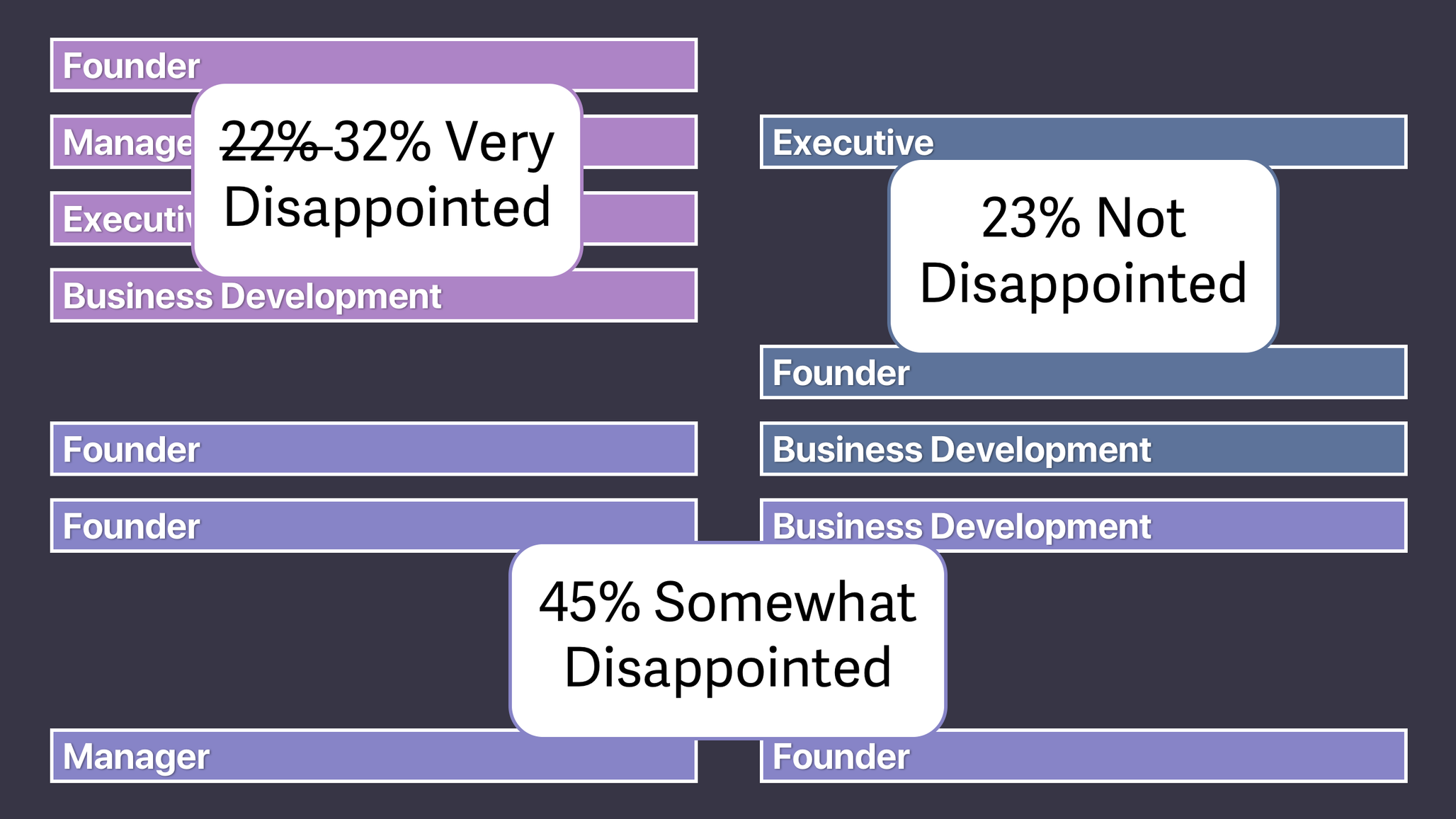

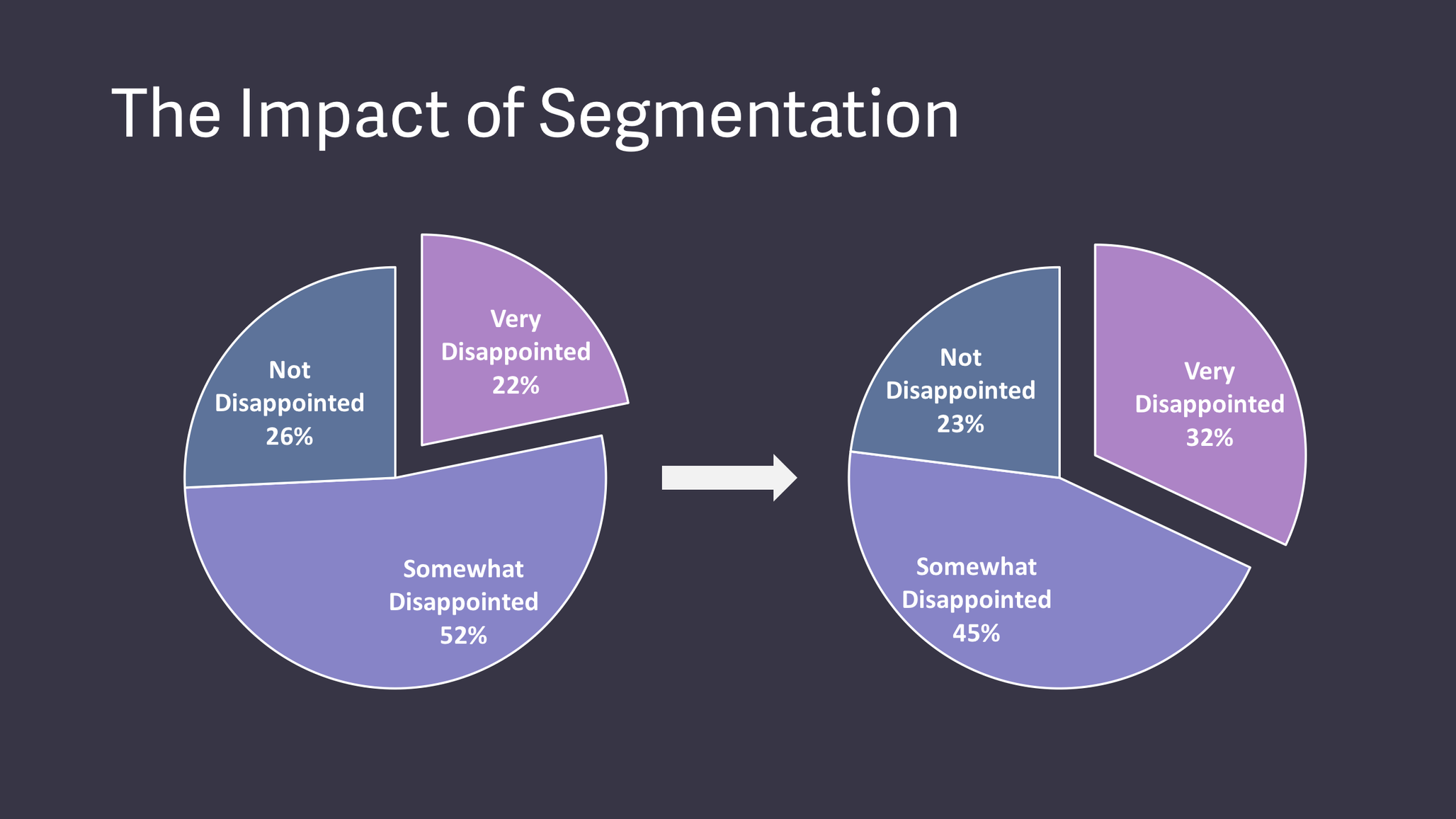

Next, we looked at the personas that appeared in the very disappointed group — the 22% that were our biggest supporters — and used those to narrow the market. In this simplified example, you can see we focused on founders, managers, executives and business development — temporarily ignoring all other personas.

With this more segmented view of our data, the numbers shifted. By segmenting down to the very disappointed group that loved our product most, our product/market fit score jumped by 10%. We weren’t quite at that coveted 40% yet, but we were a lot closer with minimal effort.

To go even deeper, I wanted to better understand these users who really loved our product. I hoped to paint as vivid a picture of them as possible, so I could galvanize the whole team to serve them better.

I turned to Julie Supan’s high-expectation customer framework as a tool to do just that. Supan notes that the high-expectation customer (HXC) isn’t an all encompassing persona, but rather the most discerning person within your target demographic. Most importantly, they will enjoy your product for its greatest benefit and help spread the word. For example, Airbnb’s HXC doesn’t simply want to visit new places, but wants to belong. For Dropbox, the HXC wants to stay organized, simplify their life, and keep their life’s work safe.

With this in mind, I sought to pinpoint Superhuman’s HXC. We took only users who would be very disappointed without our product and analyzed their responses to the second question in our survey: “What type of people do you think would most benefit from Superhuman?”

This is a very powerful question, as happy users will almost always describe themselves, not other people, using the words that matter most to them. This lets you know who the product is working for and the language that resonates with them (providing valuable kernels of insight for your marketing copy as well).

Using our customers’ words and Supan’s tips for building a profile, we crafted a rich and detailed vision of the Superhuman HXC:

Nicole is a hard-working professional who deals with many people. For example, she may be an executive, founder, manager, or in business development. Nicole works long hours, and often into the weekend. She considers herself very busy, and wishes she had more time. Nicole feels as though she’s productive, but she’s self-aware enough to realize she could be better and will occasionally investigate ways to improve. She spends much of her work day in her inbox, reading 100–200 emails and sending 15–40 on a typically day (and as many as 80 on a very busy one).

Nicole considers it part of her job to be responsive, and she prides herself on being so. She knows that being unresponsive could block her team, damage her reputation, or cause missed opportunities. She aims to get to Inbox Zero, but gets there at most two or three times a week. Very occasionally — perhaps once a year — she’ll declare email bankruptcy. She generally has a growth mindset. While she’s open-minded about new products and keeps up to date with technology, she may have a fixed mindset about email. Whilst open to new clients, she’s skeptical that one could make her faster.

With our HXC in mind, we had a tool to focus the entire company on serving that narrow segment better than anybody else. Some may find this approach too limiting, arguing that you shouldn’t narrow in on such a specific customer base early on.

It’s a commonly held view that tailoring the product too narrowly to a smaller target market means that growth will hit a ceiling — but I don’t think that’s the case.

These words of wisdom from Paul Graham explain why:

“When a startup launches, there have to be at least some users who really need what they’re making — not just people who could see themselves using it one day, but who want it urgently. Usually this initial group of users is small, for the simple reason that if there were something that large numbers of people urgently needed and that could be built with the amount of effort a startup usually puts into a version one, it would probably already exist. Which means you have to compromise on one dimension: you can either build something a large number of people want a small amount, or something a small number of people want a large amount. Choose the latter. Not all ideas of that type are good startup ideas, but nearly all good startup ideas are of that type.”

In a separate post, he drives this point home even further:

“In theory this sort of hill-climbing could get a startup into trouble. They could end up on a local maximum. But in practice that never happens. … The maxima in the space of startup ideas are not spiky and isolated. Most fairly good ideas are adjacent to even better ones.”

In essence, it’s better to make something that a small number of people want a large amount, rather than a product that a large number of people want a small amount. In my view, the product/market fit engine process of narrowing the market massively optimizes for a product that a small number of people want a large amount.

2) Analyze feedback to convert on-the-fence users into fanatics.

However, just winnowing down to HXCs is not enough. We had gone narrow, but now needed to dig deeper. Since we were below the 40% threshold, we needed to figure out why this smaller subset really loved Superhuman — and how we could bump up more users into this segment.

To get to the root of how we were going to improve the product and expand the depth of its appeal, I found it helpful to focus my efforts on these key questions:

Why do people love the product?

What holds people back from loving the product?

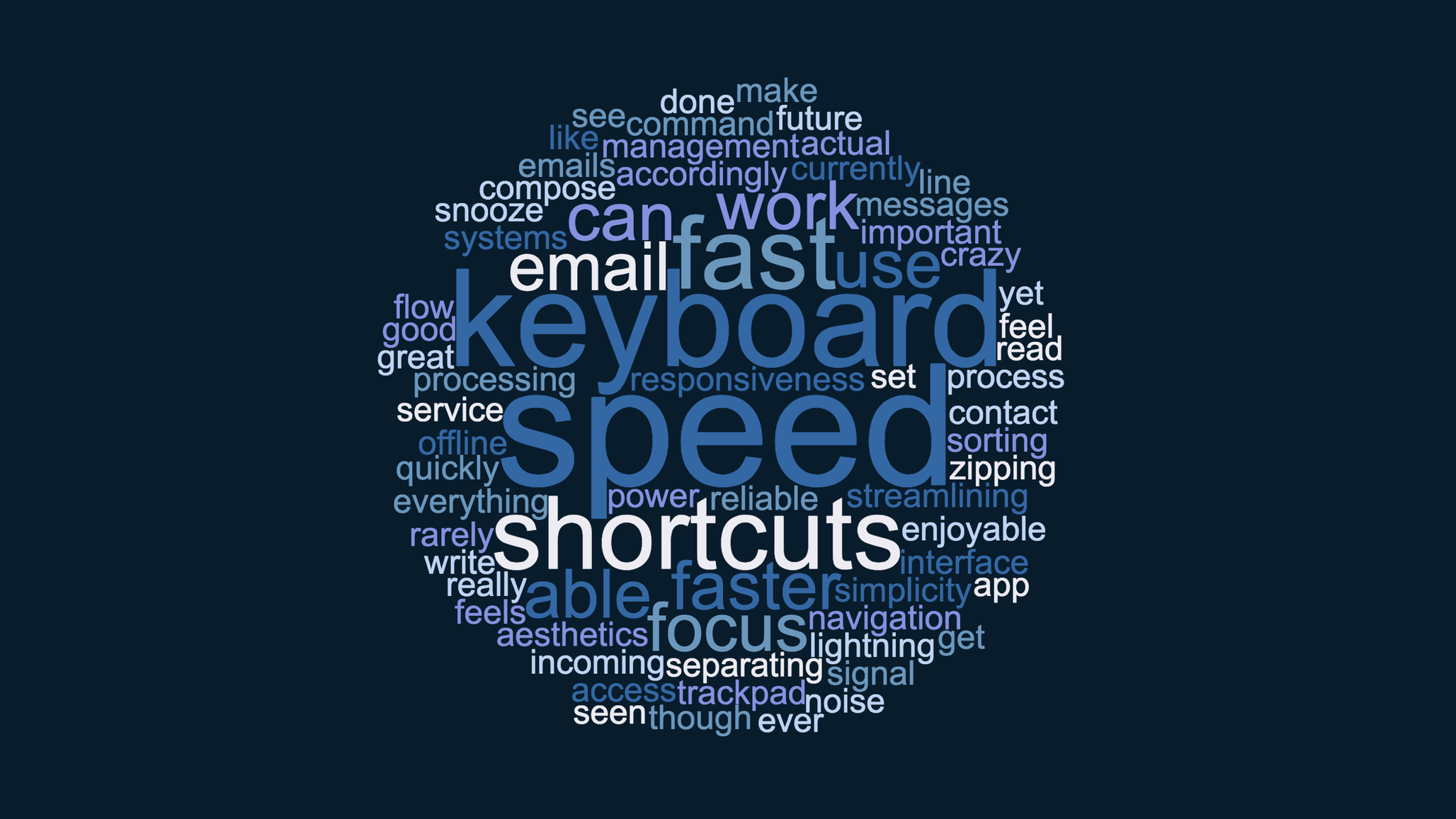

To understand why users loved Superhuman, we once again turned to the segment of those who would be very disappointed without our product. This time, we looked at their answers to the third question on our survey: “What is the main benefit you receive from Superhuman?”

Here’s a sample of some answers that stood out:

“Processing email is much faster with Superhuman for two reasons: show one email at a time and overall speed is much better than gmail. I get through my inbox in half the time.”

“Speed! The app is crazy fast, and the UX + keyboard shortcuts make me an actual superhuman.”

“Using Superhuman is so much faster than using Gmail. Not even close. And it mirrors my favorite Gmail shortcuts, so there is zero learning curve for a power Gmailer.”

“I can work through incoming email more quickly, sorting messages accordingly and streamlining my work process.”

“Speed. Aesthetics. I can do everything from the keyboard.”

“Speed and the great set of keyboard shortcuts. I rarely, if ever, have to use the trackpad.”

After throwing the responses into a word cloud, some common themes emerged: the users who loved our product most appreciated Superhuman for its speed, focus and keyboard shortcuts.

With this deeper understanding of the product’s appeal, we turned our attention to figuring out how we could help more people love Superhuman.

Our next step was somewhat counterintuitive: we decided to politely pass over the feedback from users who would not be disappointed if they could no longer use the product.

This batch of not disappointed users should not impact your product strategy in any way. They’ll request distracting features, present ill-fitting use cases and probably be very vocal, all before they churn out and leave you with a mangled, muddled roadmap. As surprising or painful as it may seem, don’t act on their feedback — it will lead you astray on your quest for product/market fit.

Politely disregard those who would not be disappointed without your product. They are so far from loving you that they are essentially a lost cause.

That leaves the users who would be somewhat disappointed without your product. On the one hand, the ‘somewhat’ indicates an opening. The seed of attraction is there; maybe with some tweaks you can convince them to fall in love with your product. But on the other hand, it’s entirely probable that some of these folks will never be very disappointed without your product no matter what you do.

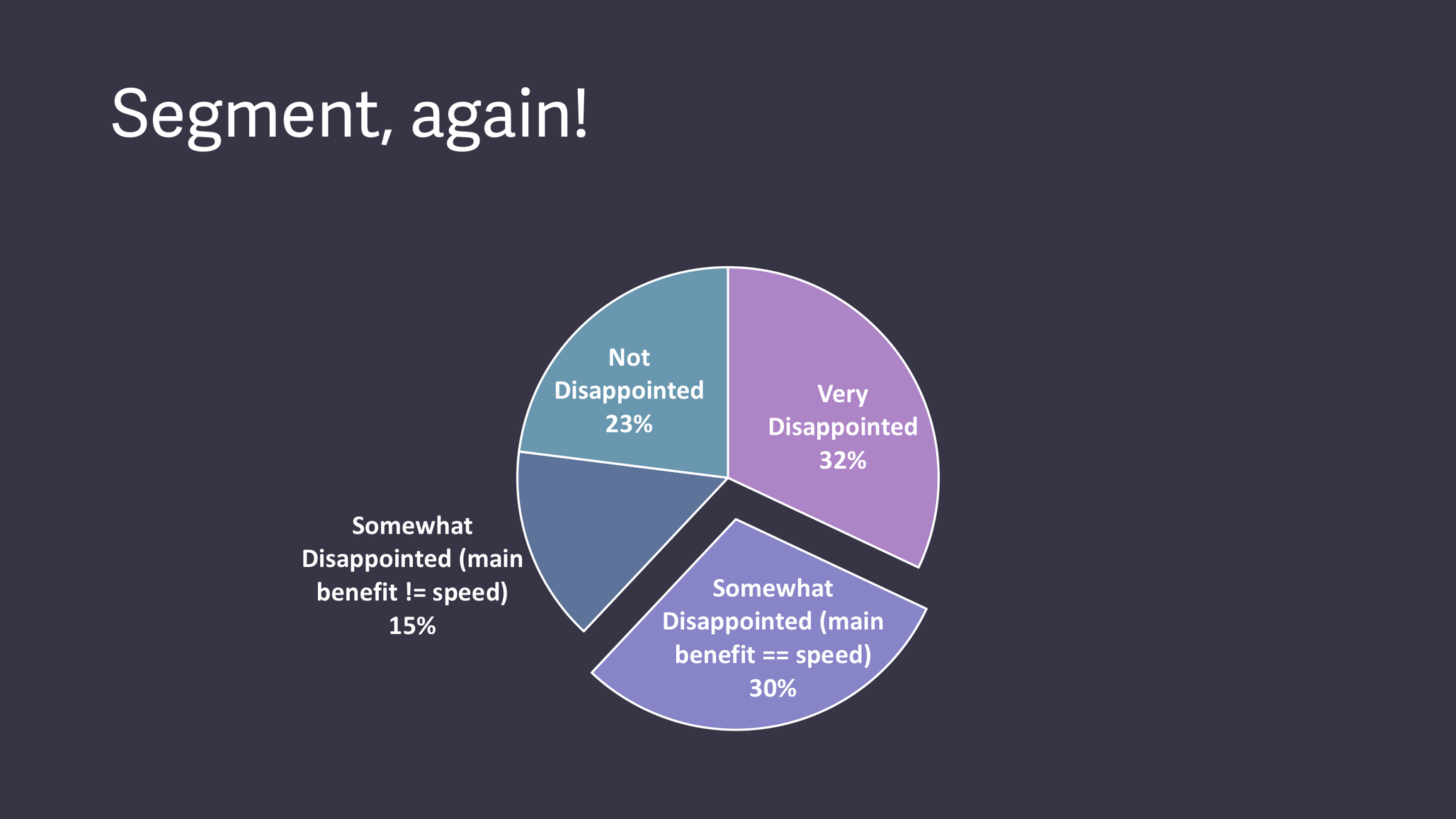

To fine-tune who we took our cues from, we segmented once again. From analyzing our third survey question, we knew that happy Superhuman users enjoyed speed as their main benefit, so we used this as a filter for the somewhat disappointed group:

After splitting the somewhat disappointed group into two new segments around speed, here’s how we decided to act on their feedback:

Somewhat disappointed users for whom speed was not the main benefit: we opted to politely disregard them, as our main benefit did not resonate. Even if we built everything they wanted, they would be unlikely to fall in love with the product.

Somewhat disappointed users for whom speed was the main benefit: we paid very close attention to this group, because our main benefit did resonate. Something — probably something small — held them back.

Focusing on this last group, we looked more closely at their answers to the fourth question on our survey: “How can we improve Superhuman for you?”

This is what we saw:

After some analysis, we found that the main thing holding back our users was simple: our lack of a mobile app. In 2015, we had taken the contrarian approach of starting with the desktop. Most emails are sent from desktop, so that’s where we thought we could add most value. We were always planning on building a mobile app, but at the beginning of our journey — like every startup — we had the chips for just one bet. In 2017, it was clear that we could no longer delay this, and that mobile had become critical for product/market fit.

Probing further, we found some less obvious and more interesting requests: integrations, attachment handling, calendaring, unified inbox, better search, read receipts and so on into the long tail. For example, as an early-stage company, internally we weren’t making heavy use of our calendar and we wouldn’t have prioritized calendaring much at all based on our own intuitions about email. Hence, this process of digging through feedback massively moved calendaring up on the product priorities list.

With a clear understanding of our main benefit and the missing features, all we had to do was funnel these insights back into how we were building Superhuman. Implementing this segmented feedback would help the somewhat disappointed users get off the fence and move into the territory of enthusiastic advocates.

3) Build your roadmap by doubling down on what users love and addressing what holds others back.

Even though we understood why users loved our product, and what held others back, it wasn’t initially clear how we were going to navigate the tension between the two when it came to committing to a product roadmap.

I eventually came to this realization: If you only double down on what users love, your product/market fit score won’t increase. If you only address what holds users back, your competition will likely overtake you. This insight guided our product planning process, effectively writing our roadmap for us.

To double down on what our very disappointed users loved, half of our roadmap was devoted to the following themes:

More speed. Superhuman was already extremely fast, but we worked to make it even faster. For example, the UI would respond within 100 ms, and search was faster than in Gmail. We pushed even further to response times of less than 50 ms, and worked to make search feel instantaneous.

More shortcuts. Users loved that they could do everything from the keyboard. So we made our shortcuts even more robust and comprehensive. We built shortcuts that no other email experience had and we started pipelining keystrokes, ensuring that everything still worked even if you typed faster than your machine could handle.

More automation. Users really valued the ability to be more efficient with their time. But we all hit the same limit: the sheer time it takes to type. So we built Snippets, a feature that lets users automatically type phrases, paragraphs, or whole emails. To save even more time, we made Snippets more robust, adding the ability to include attachments, automatically add people to CC, and even integrate with a CRM and ATS.

More design flourishes. In our feedback, we saw that users loved the design and its many small details, so we invested in hundreds of small touches to show that we care. For example, typing “–>” now automatically turns into a right arrow: →.

To gain ground with our speed-loving-yet-somewhat-disappointed users, the other half of our roadmap was focused here:

Developing a mobile app.

Adding integrations.

Improving attachment handling.

Introducing calendaring features.

Creating a unified inbox option.

Making search better.

Rolling out read receipts.

To stack-rank amongst these initiatives, we used a very simple cost-impact analysis: we labelled each potential project as low/medium/high cost, and similarly low/medium/high impact. For the second half of the roadmap, addressing what held people back, the impact was clear from the number of requests any given improvement had. For the first half of the roadmap, doubling down on what people love, we had to intuit the impact. This is where “product instinct” comes in, and that’s a function of experience and deeply empathizing with users. (The HXC profile exercise from earlier helps a great deal with developing this muscle.)

With this plan of attack outlined, we got to work, starting with the lowest hanging fruit of low cost, high impact work so we could deliver improvements immediately.

To increase your product/market fit score, spend half your time doubling down on what users already love and the other half on addressing what’s holding others back.

4) Repeat the process and make the product/market fit score the most important metric.

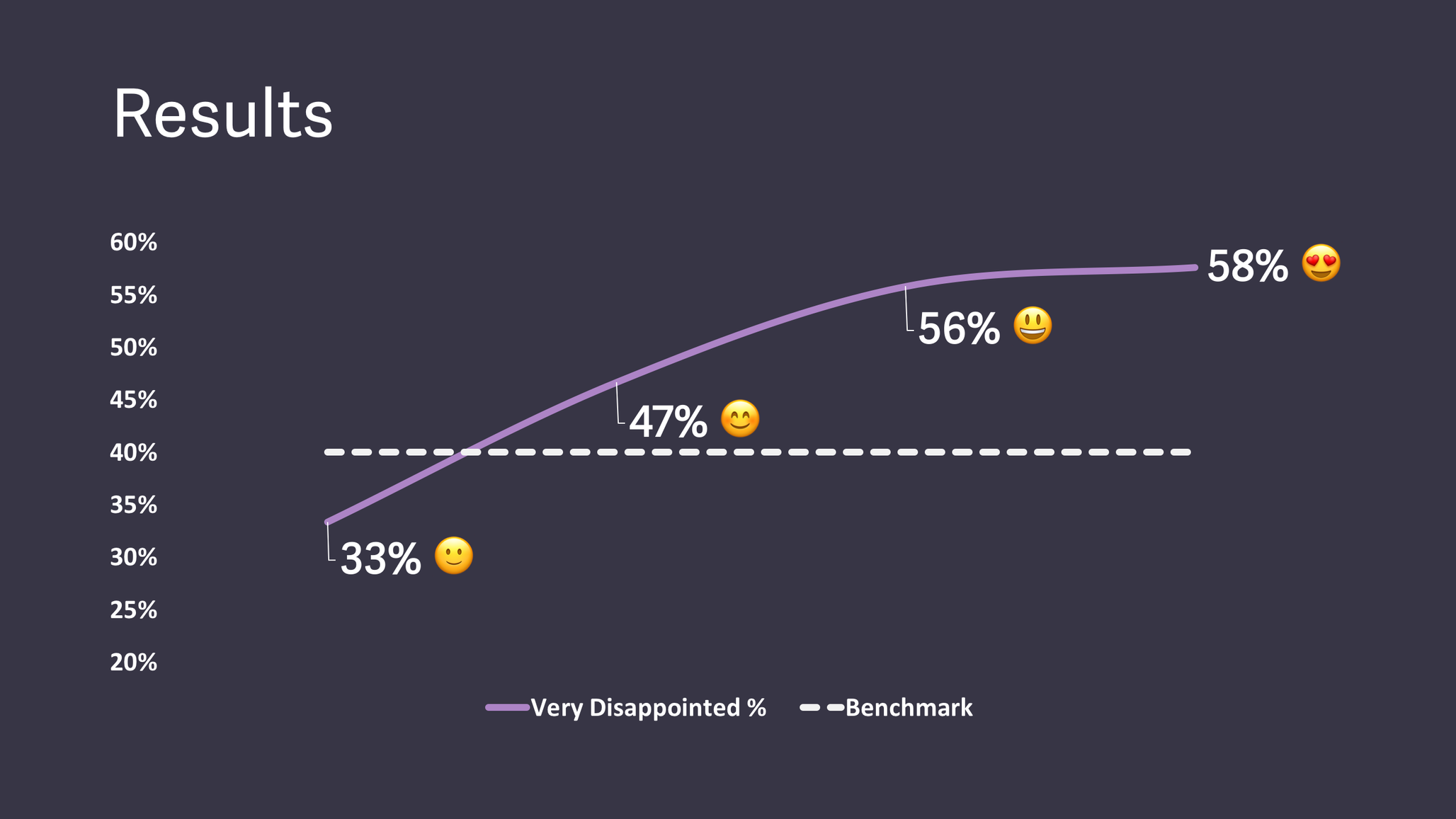

As time went on, we constantly surveyed new users to track how our product/market fit score was changing. (We were careful to ensure that we didn’t survey users more than once, so as to not throw off the 40% benchmark.)

The percent of users who answered “very disappointed” quickly became our most important number. It was our most highly visible metric, and we tracked it on a weekly, monthly and quarterly basis. To make this easier to measure over time, we built some custom tooling to constantly survey new users and update our aggregate numbers for each timeframe. We also refocused the product team, creating an OKR where the only key result was the very disappointed percentage so we could ensure that we continually increased our product/market fit.

Reorienting Superhuman around this single metric paid off. When we started this journey in the summer of 2017, our product/market fit score was 22%. After segmenting to focus on the very disappointed set of users, we were at 33%. Within just three quarters of our work to improve the product, the score nearly doubled to 58%.

And we’re not done — the product/market fit score is something that we’re going to continue to track. I think it’s always useful for startups to look at this metric, because as you grow you’ll encounter different kinds of users. Early adopters are more forgiving, and will enjoy your product’s primary benefit despite its inevitable shortcomings. But as you push beyond this group, users become much more demanding, requiring feature parity with their current products. Your product/market fit score may well drop as a result.

However, this shouldn’t cause too much anxiety, as there are some ways around it. If your business has strong network effects (think Uber or Airbnb), then the core benefit will keep getting better as you grow. If you’re a SaaS company like Superhuman, you simply have to keep on improving the product as the pool of users expands. To do that, we rebuild our roadmap every quarter using this process, ensuring that we’re improving our product/market fit score fast enough.

BRACING FOR IMPACT

In the twists and turns of following this process, I found a way to define product/market fit and a metric to measure it. Our team had a single number to rally around instead of an abstract goal that left us feeling hopeless. By surveying our users, segmenting our supporters, learning what users loved and what held them back, and then dividing a roadmap between the two, we found a methodology to increase product/market fit.

It is hard to overstate the impact of this product/market fit engine on our company. Everything we do at Superhuman — from hiring to selling and marketing to raising capital — has become significantly easier. Our team has grown to 22 people and our NPS has increased right alongside our product/market fit score. Users became noticeably more vocal about how much they loved the product, both in our surveys and on social media. Current investors started asking if they could put in more money ahead of upcoming rounds while outside investors continually ask me if they can invest.

Taking a step back to reflect on what I’ve learned from building this product/market fit engine for Superhuman, I’m left with two final takeaways:

Investors advising early-stage teams should avoid pushing for growth ahead of product/market fit. As an industry, we all know that this ends in disaster, yet the pressure for premature growth is still all too common. Startups need time and space to find their fit and launch the right way.

For any founder looking to get out of the wilderness and on the path to the ever elusive product/market fit, I’ve been in your shoes — and I hope you’ll consider retooling this engine in those proverbial startup garages to make it your own. And when you finally hit the product/market fit score you’re targeting, my advice is to push the pedal all the way down and grow as fast as you can. It will feel uncomfortable, but you’ll have the evidence you need to know that you’ll succeed.