by LENNY RACHITSKY for Lenny’s Newsletter

How to win your first 10 B2B customers

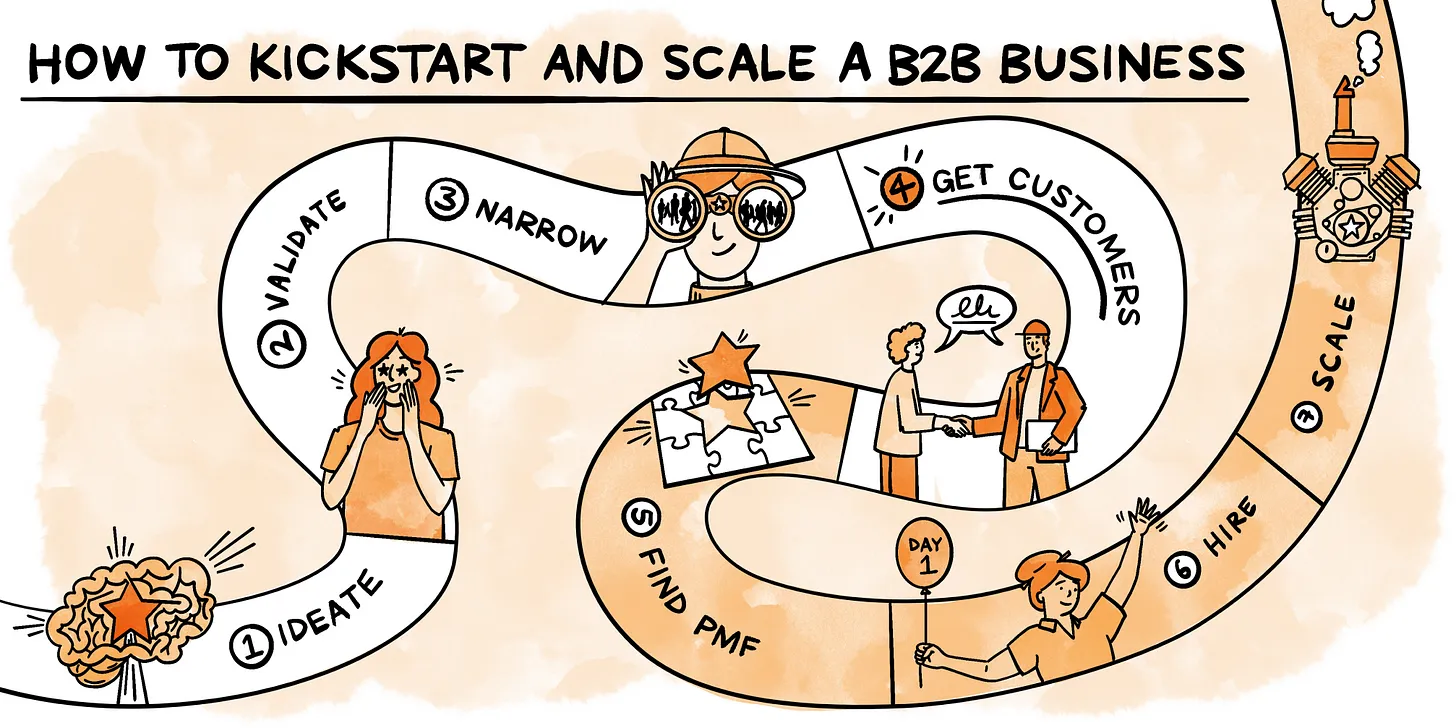

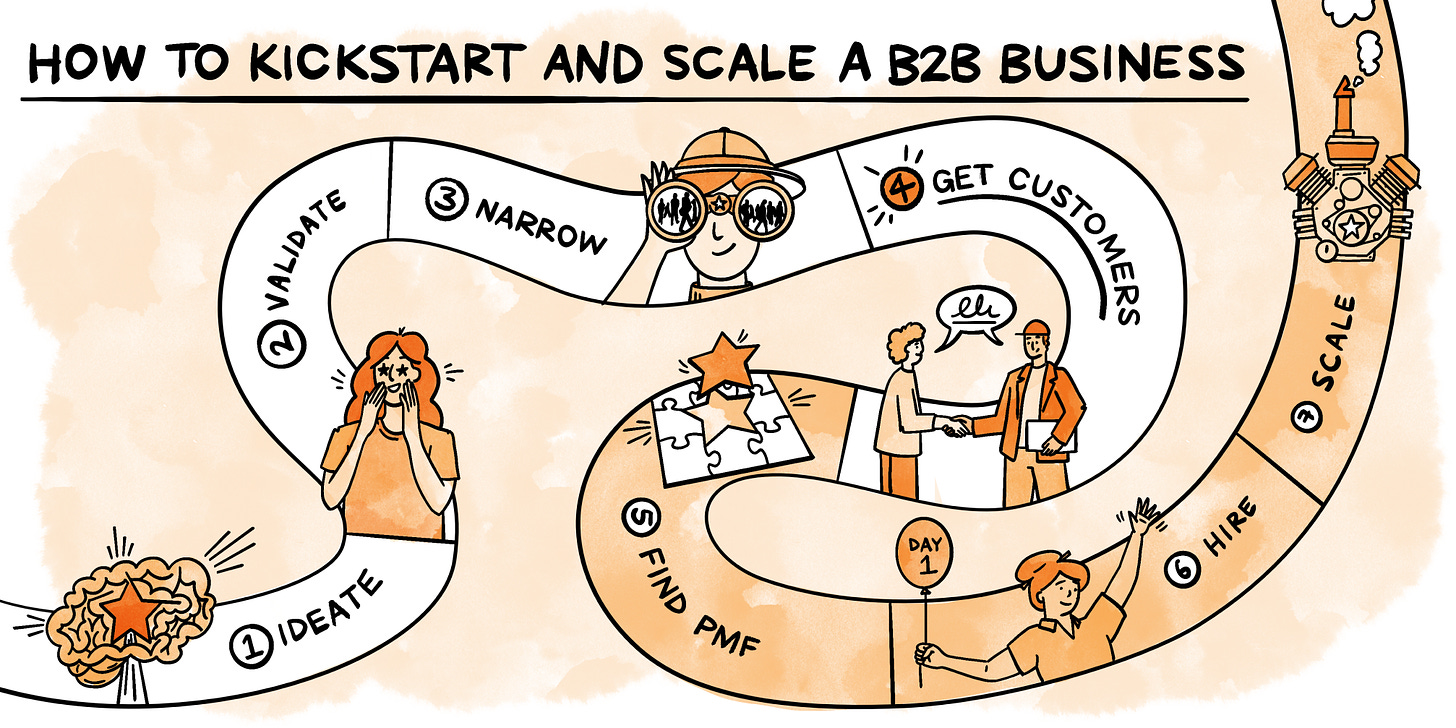

Part four of my seven-part series on kickstarting and scaling a B2B business

SEP 5, 2023

👋 Hey, I’m Lenny and welcome to a 🔒 subscriber-only edition 🔒 of my weekly newsletter. Each week I tackle reader questions about building product, driving growth, and accelerating your career.Subscribe

Welcome to part four of our series on how to kickstart and scale a B2B business:

- Part 1: How to come up with a great B2B startup idea

- Part 2: How to validate your idea

- Part 3: How to identify your ICP

- Part 4: How to find and win your first 10 customers ← This post

- Part 5: How to know when you’ve found product-market fit

- Part 6: How, and when, to hire your early team

- Part 7: How to scale your growth engine

Let’s get into it.

A huge thank-you to Akshay Kothari (COO of Notion), Ali Ghodsi (CEO of Databricks), Barry McCardel (CEO of Hex), Boris Jabes (CEO of Census), Calvin French-Owen (co-founder of Segment), Cameron Adams (co-founder and CPO of Canva), Christina Cacioppo (CEO of Vanta), David Hsu (CEO of Retool), Eilon Reshef (CPO of Gong), Eric Glyman (CEO of Ramp), Guy Podjarny (CEO of Snyk), Jori Lallo (co-founder of Linear), Julianna Lamb and Reed McGinley-Stempel (co-founders of Stytch), Mathilde Collin (CEO of Front), Rick Song (CEO of Persona), Rujul Zaparde and Lu Cheng (co-founders of Zip), Ryan Glasgow (CEO of Sprig), Shahed Khan (co-founder of Loom), Shishir Mehrotra (CEO of Coda), Sho Kuwamoto (VP of Product of Figma), Spenser Skates (co-founder and CEO of Amplitude), and Tomer London (co-founder and CPO of Gusto) for contributing to this series. Art by Natalie Harney.

Let’s jump right into it.

Here’s my recommended sequence to find your early customers:

- Start by reaching out to your network, looking for people who match your ICP

- Go cold outbound, but be strategic about it

- Tap your investors’ networks

- Participate in relevant communities—and network

- Put out compelling content and build a following online

- Get press

- Just launch

If you want to keep it really simple:

- Start with former colleagues (yours, and those of your early employees)

- Collect your investors’ contacts who match your profile and then go cold outbound (creatively)—more on this below

- Find a community where your ICPs might be hanging out, and go participate

My biggest takeaways from this step:

- None of these seven strategies scale. That’s why they work. In B2B, it always starts with hand-to-hand combat.

- Cold outbound works—if done creatively.

- PR can work, but rarely does.

- A surprising number of founders found their early customers by putting out compelling content online and first building a following.

- Y Combinator (YC) especially is very effective at helping you get early users, but not the way you’d think (as you’ll see below). Also, major shoutouts for First Round Capital.

- When joining communities, focus first on adding value to the community. No one wants to pay attention to you if you’re there just to pitch your product.

- For your first set of customers, trust is the key.

How to find and win your first 10 customers

1. Start by reaching out to your personal network, looking for people who match your ICP

Think about your friends—and their friends. Do any fit your ideal customer profile? This group will have the most innate trust (and the lowest amount of skepticism) about your idea. You won’t find a more supportive group to start with (though there’s a downside to this, as you’ll see below).

For Figma, Dylan Field reached out to design-oriented founders who he knew from previous projects:

“The early batch of alpha customers were just mostly friends, and friends of friends, of Dylan. Dylan’s the kind of guy who’s always been a mover and shaker, with connected people in the industry ever since he was a teenager. He’s just a nice, smart guy. The first company that used Figma is a company that at the time was going by the code name Krypton and now is known as Coda—Shishir’s company. Dylan and Shishir knew each other from before.”

—Sho Kuwamoto, VP of Product

Gong’s founders found their early customers through connections of theirs, along with connections of their early employees:

“All of the first dozen customers were some sort of personal connection, either through [CEO Amit Bendov] or myself or other people we later brought on. Our third or fourth employee was a part-time contractor out of the Bay Area, and he called the people he knew, like at Greenhouse Software, where he had consulted and had buddies, and asked if they wanted to try it out. It wasn’t even about selling to them, since we already knew them. But it worked.”

—Eilon Reshef, co-founder and CPO

Coda had the same experience—finding their early customers through former colleagues and early employee connections:

“My former colleague Noam Lovinsky was starting a company, and I said to him, ‘Hey, would you use Krypton [our name at the time]?’ His company started using it, and for a while, it went well. Eventually, however, this led us to rework the entire product.

Then we recruited our next set of customers. We called those the ‘Alpha 2’ customers. One was a jewelry shop run by one of our employee’s wives. Another was a tech company that my co-founder, Alex [DeNeui], started. Box, which was an early customer, came through our head of recruiting, Kenny. All were recruited one or two steps out from friends of the company.”—Shishir Mehrotra, co-founder and CEO

For Census, all of their early customers came through the founders’ networks—mostly one super-connected co-founder:

“Most of our early growth had to do with being in San Francisco and from our loose network of friends. Half of the first 10 came through Sean [Lynch, co-founder]. Everybody knows Sean, and Sean knows everyone. Sean was like, ‘Hey, let’s go talk to all these ex-Dropbox people who are at new companies and see what they think.’ The Dropbox mafia turned out to be the perfect fit for Census because most ended up at new product-led companies and wanted to do it better than Dropbox. Our pitch resonated very easily.

The other half was people who I knew. People who were doing B2B that I knew living in the Valley for a while. Fivetran is one of our earliest customers. They were in the first 10, and the co-founders of Fivetran and I went through Y Combinator 10 years ago. It was an easy conversation to have. You can skip all the niceties of doing customer discovery. And when they look at a janky demo, they’re like, ‘Yeah, dude, I remember. It’s all good.’”

—Boris Jabes, co-founder

Same for Hex:

“A few of our first 10 customers were from our network. It was people I knew in the data space. It’s one of the many reasons why I am always so confused by founders who start something that’s far outside their wheelhouse, especially in B2B, because you just have a built-in network if it’s something you know well. Glossier is an example of this. We had friends there.”

—Barry McCardel, co-founder

And Okta:

“We reached out to our networks, folks we knew in IT from Salesforce and past jobs. We networked aggressively on LinkedIn with our alma mater networks etc. We asked our angel investors and combed their LinkedIn networks. I had a target of 15 to 18 net new IT folks at different companies to talk to every month for the first six months and probably hit 85%-plus of my quota.”

—Frederic Kerrest, COO and co-founder

And Gusto:

“Gusto’s first 10 customers came from friends we knew who were just starting their businesses in California. Mostly new tech startups from our YC batch, but also non-tech small businesses (like a children’s swimming camp) that we happened to know through family and friends. We [three founders] basically went around telling everyone we knew that we’re building a modern delightful payroll and HR system and asked if they’d know someone who’d be interested in trying it out.”

—Tomer London, co-founder and CPO

And Ramp (alongside some other strategies we’ll touch on below):

“We got our first 10 customers any way we could, really. The first one was an early employee of our last startup. And they were like, ‘All right, as long as you don’t screw up my business and I can run it, I can make payments, rent it on yourselves for a little bit, but then I’ll try it because I like you.’ And there were a few other people like that, where there was a very close kind of trusting relationship.

You knew that you had us—we personally were going to go and obsess over saving your company money—and it was small enough scale and they had backups, that it was okay to do it. Later on, a lot of this came from co-building. Candid was one of our early large customers. They were at that time very high-flying direct-to-consumer. Ro is very much this kind of way, where a relationship developed over time, multiple meetings, talking about the idea and how it would come to life.

The next 40 came from a combination of friends, entrepreneurs, different people we met in the city, different finance teams, but also some level of cold or semi-cold outreach. Also, VC introductions and co-building. That was the story of the first 10 for sure. One of the first 50 was Truebill, which became Rocket Money. It was a cold email and we had met each other years before.”

—Eric Glyman, co-founder and CEO

And Notion. Also, it’s fascinating how many of these early stories connect back to Dylan and Figma 🤷♂️

“The first 10 were probably just friends and family, and founders of fellow San Francisco startups. Some we got connected to through the investors we had.

Figma was an early user of Notion, and we were also heavy users of Figma. Dylan and Ivan [Zhao, co-founder and CEO] and I have been long friends, so I know Ivan was sort of a crazy power user of Figma, giving them a ton of early feedback, and I believe that’s probably the case the other way around as well.”

—Akshay Kothari, co-founder and COO

2. Go outbound, but be strategic about it

One of the recurring themes (and biggest surprises) across my interviews is the value, and effectiveness, of going cold outbound in the early stages—cold emails, cold DMs, cold calling. But you need to be clever about how you do this. If you aren’t getting a good response, get more creative and more targeted.

Dylan Field at Figma built a custom tool to find the most influential designers on Twitter and focused all his energy there:

“We recognized for design software, there’s no choice but to go bottom-up. You cannot go top-down with designers. Designers are the ultimate arbiters of what makes a good design tool. You’re not going to tell a musician, hey, don’t use your violin that you love, use this other violin. People get really attached to their tools. We had to appeal to individual designers. And designers find out about tools not by looking at price and looking for the cheapest thing, but by seeing what other designers are using.

So Dylan actually built a custom script to find the most influential designers on Twitter and cold-DM’d them to show them Figma. That’s how it started.”

—Sho Kuwamoto, VP of Product

David Hsu at Retool used Crunchbase in an incredibly clever way:

“We were very tactical. Here’s exactly what we did—and it still works today. We bought a Crunchbase account. (In fact, we actually shared a Crunchbase account with five other companies, because we were very frugal at that point.)

We filtered Crunchbase by data points like when was the last time the company fundraised and what verticals they’re in. We didn’t want SaaS, because SaaS companies actually don’t build that many internal tools. We wanted delivery startups, we wanted fintech, we wanted stuff that’s very operationally heavy.

And then we emailed the CTO and VP of operations at these companies, because the engineering team experiences the pain of not being able to build tools, but the operations teams experience the pain of not having the tools. These were our ICPs.

We learned a lot from this outbounding exercise. That’s how we got DoorDash as our customer; that’s how we got Rappi (a few-thousand-person company) as well. Then we got Brex as a customer in this same way.”

—David Hsu, founder and CEO

Rujul Zaparde and Lu Cheng at Zip exclusively used LinkedIn—and focused on getting feedback from people versus trying to sell them right away:

“For us, we got our first 10 customers by reaching out for advice on LinkedIn. Truly, it was advice at first, until we had a clear perspective on who to go after.

We made an active decision to focus on cold outbound, versus friends. We wanted to know if this was a shitty idea or a good idea. And if we sell to friends, they might buy it because they feel bad or whatever. It’ll confuse us. So we have to get the first 10 essentially cold. They shouldn’t owe us anything. They should buy it because they see value in it, and that’s how we’ll know it’s a good idea. So they were all cold through LinkedIn.

Our first customer was a company called Deserve. There were 80 people. And I remember we did a bunch of calls with the CFO, and we were in YC approaching demo day, and we were like, ‘Dude, we really need the revenue.’ And he just felt bad, I think. And he was like, ‘All right, I’ll pay you a thousand dollars.’ And we’re like, ‘How about 10?’ And then we landed on seven, I think.”

—Rujul Zaparde and Lu Cheng, co-founders

One common thread is that you just need to hustle, as described by Gusto and Persona:

“We had a swimming instructor’s company who heard about us from her brother, who was in a startup that we knew. Also, a flower shop that Eddie [Kim, co-founder and CTO] went to buy at and asked her, ‘Hey, what are you using for payroll?’ Basically, we hustled all the way.”

—Tomer London, co-founder and CPO of Gusto

“We would build anything for anybody. The initial milestone we had was ‘As long as it has something to do with identity, we will do anything.’ I used to joke with Charles [Yeh, co-founder], ‘If we get one customer paying us anything, I’d call this a success.’”

—Rick Song, co-founder and CEO of Persona

3. Tap your investors’ networks

Though it’s not a large bucket, some startups found success leveraging their investors to find their first handful of customers, especially among YC. But not by asking for introductions—instead, by doing the hard work of digging into the investors’ own networks (including batch-mates within YC) and cold-emailing them. And not only pitching these founders but also asking them for intros to other founders who may be a fit.

Vanta used YC’s resources to source older, more established YC startups:

“We got our first 10 customers through YC. This is why we did YC. But not people in the actual batch, because companies in the batch were so early-stage and did not think about SOC 2s back in 2018. They do now, though.

I went through the list of old YC companies, worked with our partner to prioritize them, and wrote outbound emails to the founders. I went through Bookface, the YC internal forum, and emailed anyone who’d ever said the word ‘compliance’ on Bookface in the prior decade. Literally. Somewhere in there, we got our first 10 customers.”

—Christina Cacioppo, founder and CEO

Amplitude similarly used YC, but not to get intros to batch-mate founders. Instead, to get into a network of product people who matched their ICP:

“Our very first few customers were connections through investors and other folks at YC. One mistake that YC companies make is trying to sell to other people in their batch. Those are not real companies. They don’t have money. A YC company is a speculative investment, not a business yet. You want to go sell someone who’s a real business and figure out how to solve their problems.

The very first community we got word of mouth in was the ex-Zynga product managers who had gone on to build their own companies. Matt Ocko, who is an investor in us through Data Collective, introduced us to this guy Bret Terrill, who is the CTO and co-founder of Super Lucky Casino and was ex-Zynga. He got excited, and then from that, other folks in the Zynga community heard about us. He posted in their Facebook group or something.”

—Spenser Skates, co-founder and CEO

Sprig tapped both YC and First Round’s unique internal resources to go cold outbound:

“Our first 10 customers were all from cold emails to YC companies. One of these emails led to a meeting with Thunkable, which ended up being our first customer that I had no connection to. They came over to our office, I did a demo, and they installed right there. A week later, I came back and helped them figure out all these issues and usability challenges, and they asked how much it cost. That was the first full sale where it was not a friend’s friend, or not my friend, or not someone I already knew or might know me.

This is also where I love First Round Capital. I’ll sing their praises for the rest of my life. They have an SDR program (they don’t call it that; they call it a customer discovery program), but they basically have someone who is sending cold emails to your target customers for you, aiming to get you five meetings a week. Our partner, Bill Trenchard, told us, ‘We’re going to get you five meetings a week for exactly who you want to talk to, and then we’re going to meet with you every two weeks to talk about the feedback. We’re going to talk through the feedback, see what’s working, and you’ve got to get the company to a million ARR. Then you can hire salespeople.’”

—Ryan Glasgow, CEO

And Carta found lots of success finding customers through their investors (likely because their product was for founders and investors):

“Our very early customers came from two places:

- The angel investors in our company: Andy Palmer from Tamr was an investor in eShares [now Carta] and brought it into his company early on.

- Sister portfolio founders: We had this personal connection to them through our investors.

Other than that, it was just working the network.”

—Josh Merrill, ex-CPO

4. Participate in communities, and network

A surprising number of startups found some of their early customers by old-school networking and community building. This includes participating both in offline and online communities, and sometimes creating your own community.

The founder of Snyk went to where their ICP users were spending time—meetups, events, and online communities:

“Since we were trying to get developers to take on a responsibility they’ve historically not embraced, it was critical to make the product extremely low-friction and focus on getting them using it.

Therefore, we initially launched a freemium beta product, promoted it across open-source project maintainers and in dev communities, and didn’t have a paid version for nearly a year. The first users of the product came from meetups and conference-based events, online content, and proactive reach-outs to our networks, dev thought leaders, and open source maintainers. We pretty quickly got to thousands of users, and a year later, the first (tiny) customers came out of that user base.”

—Guy Podjarny, founder and CEO

Plaid similarly found success tapping online forums and meetups where developers and PMs spent time:

“We mostly grew through word of mouth in the developer and product manager community. We invested in meeting founders of fintech companies, learning their problems, and seeing how Plaid could help. Lots of time spent on forums, IRC, meetups, and working with startup accelerators.”

—Zach Perret, co-founder and CEO

The founders of Databricks went further and organized their own events and community:

“In the early Berkeley days, we would put on these events where we would say, ‘Come and do a hackathon with us and use our open source software.’ And we would sort of handhold them and say, ‘Oh, if you want to try to do machine learning, let’s help you figure this out.’ These were called AMP Camps. AMP was the name of the lab we were in at the time: Algorithms, Machines and People, because the lab was focused on using algorithms and then machines and then people, sort of the mix of those three. We put on these AMP Camps and they were popular, and we thought we were world-famous rock stars because we could get 70 people to come to it. About 70 people in the room just here using our software. I mean, it’s like, can you believe it?”

—Ali Ghodsi, co-founder and CEO

Persona found great success at First Round Capital’s networking events:

“Our first customer actually was a friend of a friend’s vape shop; they needed help with age verification.

Some of our other early customers came through First Round. We would go to every one of their events, and whoever seemed they had some identity needs, we pitched them. Urban Sitter came through this. I had met them at one of these First Round events, and I think their founder had brought up something about identity verification, and all of us jumped on that deal.”

—Rick Song, co-founder and CEO

5. Put out compelling content and build a following online

I was surprised by how many founders found their early users from their online presence. Some started sharing content online before they started the company, and some after.

The founder of Front went big with content:

“We ultimately had 3,000 people signing up for our beta (mostly B2B). My approach was to inundate the market with content—write interesting content, post on Hacker News, post on Twitter, etc.) and see who signs up.”

—Mathilde Collin, founder and CEO

The founders of Linear started building buzz and a following on Twitter early on, building on their existing Twitter following:

“A couple of our first 10 customers were through friends, but really, most of our early growth was building a wait list through Twitter. When we went full-time on the idea, we put out an announcement on Twitter to a landing page with an email signup. We had a good amount of Twitter followers among the three founders, so we were very privileged there.”

—Jori Lallo, co-founder

As Hex’s founder says, it’s never too late:

“We started putting out a lot of content early on, writing about the problem we were solving and building an audience. That helped us build a wait list. Then we started sending out feature update emails as we were releasing features and got back replies, ‘This looks sweet. I’d love to try it.’ And then we’d spin up accounts for people, and they started using it and went from there.

Even with a large wait list, it took us a while to get to 10 customers. With a product that’s technical and complex, it takes a while to build a surface area big enough that you just feel good getting people on.

Also, at some point, we saw this tastemaker effect where there were certain people who started using the product who would tell people, and so other people started using it. If we got some of the right people using it, we would get sort of a viral adoption effect. That was really cool to see happen.”

—Barry McCardel, co-founder

6. Get press

Three startups I looked at had meaningful success with early PR.

Amplitude:

“Soon after, we did a TechCrunch launch in early 2014, and we got a handful of customers through that. Keepsafe came through that. Normally PR is a terrible channel. You need to grow through communities and customers hearing about you through word of mouth.”

—Spenser Skates, CEO and co-founder

Canva:

“We had a fair bit of press based on our very first funding round. Press loved writing about funding, so anytime you can talk about funding, it was easy to get a story.”

—Cameron Adams, co-founder and CPO

Slack:

“With help from an impressive press blitz (based largely on the team’s prior experience—i.e. use whatever you’ve got going for you), they welcomed people to request an invitation to try Slack. On the first day, 8,000 people did just that; and two weeks later, that number had grown to 15,000. The big lesson here: Don’t underestimate the power of traditional media when you launch.”

—Stewart Butterfield, co-founder and former CEO (via First Round Review)

7. Just launch, and wait for users to come to you

Sometimes you build it and they do come, like in the case of Segment, Stytch, and Loom.

Segment:

“We just launched on HN. You can still read the post. In the early days, we got a lot of engineers trying out the product on their side projects. They told us what they’d need to bring it into their companies. We just sort of levered our way up into bigger and bigger markets that way. The short answer is launch, launch, launch.”

—Calvin French-Owen, co-founder

Stytch:

“The first random (i.e. non-friend) internet user who used the product was a pretty exciting one. Our public beta had not even been released yet. This one guy, Jon Ma, who ran Public Comps, had reached out on our site and had been one of the few I gave beta access to. We didn’t really expect anyone to deploy it into their production environment on a real product. We had a 20-minute conversation, gave them the API keys, and then eight hours later, we saw production traffic from them. Our eng team was like, did we know somebody was going to go into production?!

After that, we were approaching launch and somebody was about to leak the story on us, so we just ended up publishing on our blog that we had raised the seed. Chetan [Puttagunta], our partner at Benchmark, retweeted it, and we started getting a lot of signups for demos, even if they didn’t have immediate use cases, just out of interest. Something like 40% to 50% converted to demos, and then maybe 20% of those converted to actually onboarding with the product.”

—Reed McGinley-Stempel and Julianna Lamb, co-founders

Loom:

“We launched on Product Hunt and had thousands of people who downloaded the extension by day’s end.”

—Shahed Khan, co-founder

Canva did all of the above 🤣👏

“We had a big wait list that we had built up over time. That wait list had taken two years to build up, and it was all sorts of random connections, people we’d met at conferences, people that we’d done user testing with, friends, family, everyone. That wait list was probably 10,000 people by the time we launched.

We’d laid the seeds for it, and then off the back of those seeds, we lined up a bunch of press for launch day, and we’d done a bunch of embargoes and gotten interviews with TechCrunch and ZDNet and a few other outlets. We’d given them a pre-demo of what the product was going to be on launch day, and then scheduled them all to launch at launch night.

Here in Australia, it’s a bit different dealing with American press, because all these launches are basically at midnight in Australia. We stayed up all night watching the press come out and watching our real-time Google Analytics board as well, expecting all the people to roll in. We also sent out an email to our wait list saying the product was now ready, and we’d set up a big dashboard screen with Google Analytics on it so that we could see the thousands and millions of users rolling in on day one.

Unfortunately, it didn’t quite happen that way. We had one user drip in, and then another user drip in five minutes later, and the flood of users didn’t quite materialize on day one. I remember feeling slightly dejected that night.

We had put so much effort into the launch. For the week beforehand, we basically had no sleep as we were crunching bugs and polishing the product. And the number of people we got that night, particularly from the press, was a bit anticlimactic. I think it is really hard to convert press into actual users of your product, often because the articles don’t necessarily link to your product. People often just read about the product in the press and don’t actually make that leap across to your site. So it was quite a slow burn. It was by no means an overnight success.

I think in that first week we probably got about a couple thousand signups, and then the week after that we got 5,000, and it slowly grew and grew.

Over time, there was never one silver bullet. It’s always just bits and pieces and that slowly agglomerates into a full acquisition channel. I remember one time, one of my old sites on my personal website started getting a huge amount of traffic for some weird reason. It was actually this Daft Punk visualization that I’d created, and it turned out that Daft Punk had released or teased an album at Coachella and someone had linked to my site, and it had started getting millions of visitors. So we actually put up a banner at the top of that which pointed to Canva, and I think we got more visitors via that than we actually got through our TechCrunch article. You try out all these weird and wonderful things to get traffic in the early days.

We were quite fortunate in that our early user base was a very talkative user base, so the people who were using Canva and the people who we had user-tested with and built community up with were social media managers and bloggers, so people who love to talk about the tools that they’re using and build an audience based around that. So a lot of our early Canva users were in that mold, and they were our best advocates. They were tweeting about Canva, they were writing blog posts about it, and that enabled the first six to 12 months of Canva’s growth.”

—Cameron Adams, co-founder and CPO

Important takeaway: Trust is your secret weapon

If you look back at the sequence above, it’s essentially a series of concentric circles with increasing distance from the founder. Or, put another way, decreasing levels of trust.

Takeaway: Start with the channels that have the most innate levels of trust, and work your way outward.

Here’s Sho Kuwamoto’s take on the importance of trust for Figma’s early customers:

“It’s all a matter of trust. Somebody I trust is going to say, you should use this tool. I’m going to trust it way more than if they’re marketing people saying that you should use this tool. And so we tried to make sure that we understood those people and so we got them in early, but we also did a good job of trying to listen to them too. They’d give us feedback and they’d say, this is good and this is not good, and we take that seriously.

As soon as the word got out: oh, there’s this new tool, it’s by this Greylock-funded company, they’re going to change everything about how design works; people are like, oh, I’ll sign up. So we already had a good list of people, and it was a matter of us reaching out to them to say, hey, would you like to be in the beta? And so on.

They ask other designers, you’re like: hey, I just found this tool, it’s amazing; you should check it out. Or, oh, I hear that Airbnb is seriously using Figma. What the hell? We should check it out. That’s how it happens. So we deliberately tried to understand, well, who are the people that people listen to the most? We actually scraped Twitter to understand how people are connected to people on Twitter.”

Same story for Ramp from Eric Glyman (co-founder and CEO):

“They were like, ‘All right, as long as you don’t screw up my business and I can run it, I can make payments, rent it on yourselves for a little bit, but then I’ll try it because I like you.’ And there were a few other people like that, where there was a very close kind of trusting relationship.

You knew that you had us—we personally were going to go and obsess over saving your company money—and it was small enough scale and they had backups, that it was okay to do it.”

And Census, from Boris Jabes (co-founder and CEO):

“Fivetran is one of our earliest users. They were in the first 10, and the co-founders of Fivetran and I went through YC 10 years ago. It was an easy conversation to have. You can skip all the niceties of doing customer discovery. And when they look at a janky demo, they’re like, ‘Yeah, dude, I remember. It’s all good.’”

And Salesforce, from Marc Benioff, founder and CEO (source):

“It was challenging to convince prospects to try our service, and it was especially challenging to convince the first one. Most people don’t want to be the first to take a giant risk. Realizing that truism was pivotal. We finessed our strategy to target pioneers who saw an opportunity to participate in something new and exciting.

That first pioneer came in the form of Blue Martini Software, one of the small software companies in which I had previously invested. I knew I was asking for a favor when I called the founder, Monte Zweben, but I also knew I was offering something that he really needed.”

And finally, Shishir Mehrotra, co-founder and CEO of Coda, who shares a strong perspective on targeting friends early on:

“How important is it that your early customers not be connected to the company? A lot of people tell you it’s super-important for them not to be connected. I don’t buy that. I think that certainly for a product like Coda, you can’t force anybody to use it. If they don’t like it, they will stop using it, regardless of how close they are to you. And I think the ability for them to give you honest feedback is actually higher if they know you.”

This problem is especially hard for certain spaces, as Rick Song found when starting Persona:

“Early on, we knew very quickly that we couldn’t sell to anyone large. We were just too small. Size truly is a consideration, especially for certain types of products like security. They’d have to be insane for a mature company to work with a startup like us to build a PII system, especially one that wouldn’t be hosted on their own system. But this limitation was also very helpful, to be constantly thinking through, ‘Why would this person buy us?’”

Again, here’s the sequence:

- Start by reaching out to your network, looking for people who match your ICP

- Go outbound, but be strategic about it

- Tap your investors’ networks

- Participate in communities—and network

- Put out compelling content and build a following online

- Get press

- Just launch