Data has become the lifeblood of modern marketing. It now touches almost every aspect of the marketing function. But using the wrong data (or the right data in the wrong way) can lead to ineffective and costly decisions. Here’s one mistake marketers need to avoid.

Fueled by the explosive growth of online communication and commerce, marketers now have access to a huge amount of data about customers and potential buyers. Astute marketing leaders have recognized that this ocean of data is potentially a rich source of insights they can use to improve marketing performance. Therefore, many have made – and continue to make – sizeable investments in data analytics.

Data undeniably holds great potential value for marketers, but it can also be a double-edged sword. If marketers use inaccurate or incomplete data, or don’t apply the right logical and statistical principles when analyzing data, the results can be costly.

The reality is, a variety of potential pitfalls lurk in almost every dataset, and many aren’t obvious to those of us who aren’t formally trained in mathematics or statistics. An incident that occurred during World War II dramatically illustrates a data analytics pitfall that is still far too common and not always easy to detect.

The Case of the Missing Bullet Holes*

In the early stages of the war in Europe, a significant number of U.S. bombers were being shot down by machine gun fire from German fighter planes. One way to reduce these losses was to add armor plating to the bombers.

However, armor makes a plane heavier, and heavier planes are less maneuverable and use more fuel, which reduces their range. The challenge was to determine how much armor to add and where to put it to provide the greatest protection for the least amount of additional weight.

To address this challenge, the U.S. military sought help from the Statistical Research Group, a collection of top mathematicians and statisticians formed to support the war effort. Abraham Wald, a mathematician who had immigrated from Austria, was a member of the SRG, and he was assigned to the bomber-armor problem.

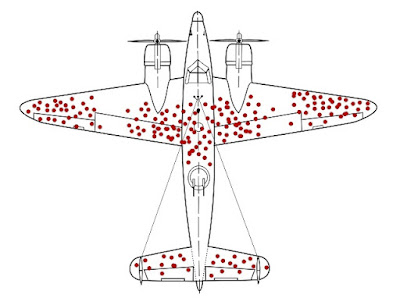

The military provided the SRG with data they thought would be useful. When bombers returned from missions, military personnel would count the bullet holes in the aircraft and note their location. As the drawing at the top of this post illustrates, there were more bullet holes in some parts of the planes than others. There were lots of bullet holes in the wings and the fuselage, but almost none in the engines.

Military leaders thought the obvious solution was to put the extra armor in the areas that were being hit the most, but Abraham Wald disagreed. He said the armor should be placed where the bullet holes weren’t – on the engines.

Wald argued that bombers returning from missions had few hits to the engines (relative to other areas) because the planes that got hit in the engines didn’t make it back to their bases. Bullet holes in the fuselage and other areas were damaging, but hits in the engines were more likely to be “fatal.” So that’s where the added armor should be placed.

An Example of Selection Bias

The mistake U.S. military leaders made in the bomber incident was to think the data they had collected was all the data that was relevant to the problem they wanted to solve.

The flaw in the bomber data is now called a survival bias, which is a type of selection bias. A selection bias occurs when the data used in an analysis (the “sample”) is not representative of the relevant population in some important respect.

In the bomber case, the sample only included data from bombers that returned from their missions, while the relevant population was “all bombers flying missions.”

So why should B2B marketers care about bullet holes in World War II bombers? Because it’s very easy for marketers to fall prey to selection bias. Here are a couple of examples:

- Suppose you survey your existing customers to identify which of your company’s value propositions are most attractive to potential buyers. Because of selection bias, the data from such a survey may not provide valid insight into what value propositions would be attractive to other potential buyers in your target market.

- Suppose you develop maps of buyers’ purchase journeys based primarily on data about the journeys followed by your existing customers and by non-customers who have engaged with your company. Because of selection bias, these journey maps may not accurately describe the buyer journeys followed by potential buyers who never engaged with your company.

Selection bias is a troublesome issue because, like all humans, we marketers tend to base our decisions on the evidence that’s readily available or easily obtainable, and we tend to ignore the issue of what evidence may be missing. In many cases, unfortunately, the evidence we can easily access isn’t broad enough to give us valid answers to the issues we are seeking to address.